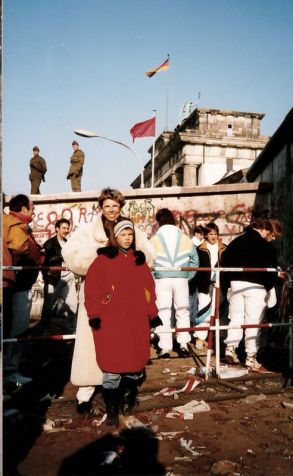

Annika Hinze with her mother in front of the Berlin Wall by the Brandenburg gate as East German soldiers stand guard. Courtesy of Annike Hinze

By Richard Bordelon

Since 1961, the Berlin Wall had been a reality for the people of both East and West Berlin. The Wall’s fall on Nov. 9, 1989 shocked many people, both in Germany and abroad.

“I had never seen Berlin without the wall,” said Annika Hinze, an assistant professor of political science at Fordham, who was born and raised in West Berlin. “I was born into a divided city — it was all I knew.”

In 1989, the Eastern Bloc experienced a general thawing of tensions due to the policy of openness (glasnost) fostered by Mikhail Gorbachev, the then-Premier of the Soviet Union. However, an error made by the East German bureaucracy was a catalyst for the immediate opening of the border between the two Berlins. On the evening of Nov. 9, Günter Schabowski mistakenly announced that East German citizens could immediately cross into the West with the correct authorization.

This statement encouraged many Berliners (both East and West) to rush to the borders and to the Wall. However, others dismissed the highly unusual statement.

“Until that point, there had been no real concessions by the [East German] functionaries,” Hinze explained via email, “and my mom thought this to be yet another fluke, so she turned off the TV and went to bed.”

That morning, the 10-year-old Hinze and her family woke up to a very different Berlin. “I remember brushing my teeth that morning,” Hinze recalled, “looking into the mirror and trying to savor the historic moment because I was convinced that they were probably going to close the wall again any second.”

The Wall did not close. Although East and West Germany remained two separate countries until late 1991, Berliners were able to explore their entire city for the first time since the Wall was erected in 1961. Hinze and her family made many excursions into the former East Berlin. Hinze explained that her parents enjoyed these trips, but, as a 10-year-old child, she felt very differently.

“I hated those excursions!” she said. “I remember everything looking very gray and depressing. It was wintertime, too, which made everything worse.” Until this point, West Berlin had been completely isolated from the rest of the West, surrounded by East Germany.

Many East Berliners also seized the opportunity to visit the Western sector that lay just beyond the Wall. They drove their infamous Trabbant (Trabbi) cars into West Berlin to explore the other half of the city and to shop. West Berliners noticed the influx of East Berliners, particularly due to the incredible number of Trabbis that began to appear in the West.

“There was also this cliché among West Germans that the East Germans were all shopping at Aldi, a cheap German supermarket,” Hinze explained. Although this probably was not completely accurate, East Berliners did begin to shop in the West more often.

However, the camaraderie between East and West Berliners did not last forever.

“Over time, each side became annoyed with the other one,” Hinze said. “The honeymoon didn’t last forever!”

The new, larger city was an exciting prospect for young people at the time. “As we turned from children into teenagers, my friends and I ‘conquered’ the East!” Hinze recalled. “All the ‘cool’ bars, clubs and neighborhoods were there! Berlin turned into a completely different city from what it had been.”

Now, 25 years later, the fall of the Wall remains one of the most important events in the life of Berliners. According to Hinze, this event retains significance due to the popular effort that brought down the Wall, which also created an identity of resilience. “The wall fell because of the people all over East Germany, but also because of all the Berliners from the East and the West who gathered on the night of Nov. 9 at all the border checkpoints in the city and finally reached critical mass and just basically ‘overran’ the border,’” she said. “It was a revolution of the people, a really wonderful, wonderful event in a city that had seen so much tragedy over the course of the 20th century!”

The fall of the Berlin Wall was not simply a political event; it was deeply personal, changing the lives of most Berliners.

“Over the past 25 years, I have met many special people whom I would have never met if the wall had not come down that fateful night!” Hinze recalled. “This changed the course of my life, forever!”

_______

Richard Bordelon is the Opinion Editor at The Fordham Ram