One day, while flipping the channels during my fifth grade school vacation, I came across a program on which an older man wearing thick glasses and a sweater was talking about the best movies of 2003.

Little did I know that over the next 10 years this man, Roger Ebert, would not only give me a new appreciation for the movies but also be an inspiration to me because of how he soldiered on in the face of adversity.

Ebert, who died on April 4 at the age of 70, was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times for 46 years. He was the first film critic to win a Pulitzer Prize and is the only critic to have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

I, like many others, first discovered Ebert through his television show. Every week I watched as he and his partner, Richard Roeper, debated the merits of the week’s new releases. I knew that any movie that got a “thumbs up” would instantly get on my list, but I also relished when one got a “thumbs down” because I knew that meant I would hear Ebert’s oratory mercilessly berate the latest flop.

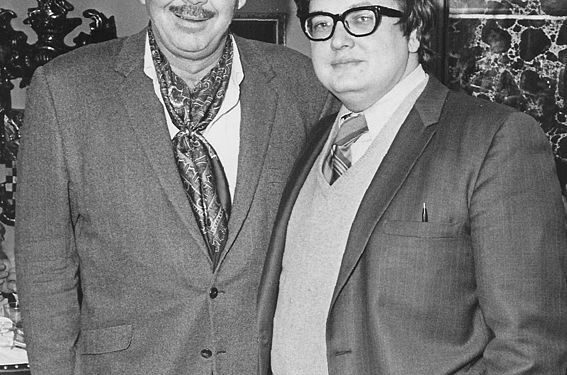

Once YouTube came into the picture, I discovered a treasure trove of clips of Ebert talking movies with his original sparring partner, Gene Siskel, which helped me to discover new film gems. I watched old and new classics like Citizen Kane and Fargo because Siskel and Ebert strongly recommended them, and they never steered me wrong.

Finally, when Ebert launched a website, I was able to read his reviews as they appeared in print. Ebert’s entire catalogue was and still is online, and reading these masterpieces of criticism showed me a new way to write about movies. He was a journalistic hero and one of my main inspirations in my own cultural writing.

Ebert proved himself a hero in a new way in the last years of his life. He battled cancer in 2002 and 2006. Treatment for the second bout, in his salivary gland, involved removing part of his jaw, rendering him unable to speak. Ebert had to quit his television show, and I, along with his many other fans, wondered if he would ever be able to bounce back.

He did indeed recover, and found two new voices in the process. In the literal sense, he used a computerized voice to communicate, which he demonstrated in several television appearances. More amazingly, he discovered a new critical voice on the Internet. He started a blog, on which he not only posted about movies but also wrote very openly and eloquently about his illness. He may have been separated from daily life because of it, but he could now “live more in [his] memory and discover that a great many things are safely stored away.”

Ebert also embraced social media. He amassed 100,000 likes on Facebook and 800,000 followers on Twitter. Here he was more playful posting things like his entry in The New Yorker cartoon caption contest, which he entered every week. His many online platforms are worth exploring as a testament to his strength in the face of illness.

Roger Ebert’s reaction to a crippling diagnosis was to keep on living. His bravery makes me want to be a better person, and I respect him for what he taught me about life as much as for his great critical work.

Two days before his death, Ebert posted a blog entry saying he was taking a “leave of presence,” which meant that he was slowing down but still going to work. He ends the entry with this: “Thank you for going on this journey with me. I’ll see you at the movies.”

Mr. Ebert, thank you for letting me go on the journey with you. I’ll see you at the movies.