By Elizabeth Smislova

A high-pitched and eerily beautiful harmonica sound flooded my ears as I got the New York Times app alert saying Bob Dylan received the Nobel Prize in Literature. It was one of those perfect moments when everything in the universe seemed to line up as it should. The musical genius I listened to received his well-deserved recognition. For me, listening to Dylan’s voice is like talking to an old friend or warming up by the fire with family. There is comfort in hearing someone describe feelings I have but cannot name, and reassurance in knowing someone feels life so deeply and acutely to write such lyrics as Dylan does.

His 1963 album, The Freewheelin’, has been the soundtrack of my life, in both trying and joyful times. The album features many of his well-known songs, including “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which asks, “Yes, and how many ears must one man have before he can hear people cry? Yes, and how many deaths will it take ’til he knows that too many people have died? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.”

He does not shy away from conveying the reality that people often do not acknowledge nor do his lyrics sugarcoat life. My favorite song on the album is “Girl from the North Country,” which is not an exception to Dylan’s tendency for sad songs. In it, Dylan asks someone to check up on someone who “was once a true love of mine.” It is one of the most romantic songs I have ever heard because the couple is not in love anymore, but he still thinks of her and cares about her. It is about a past love, but is somehow hopeful and makes you want to believe in love again.

Another gem on the album is “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” which tells of a breakup with a girl who did not love him in the way he wanted. The lyrics are, “You could have done better but I don’t mind. You just kinda wasted my precious time, but don’t think twice, it’s all right.” He is genuinely blunt, a refreshing change from music that idealizes dramatic breakups and relationships. “Talkin’ World War III Blues” is an incredibly interesting and funny song that describes a dream about the only one left after World War III. In the end, he realizes everyone has the same dream and says the famous lines, “Half of the people can be part right all of the time, some of the people can be all right part of the time, but all of the people can’t be all right all of the time. I think Abraham Lincoln said that. ‘I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours.’ I said that.” Here, Dylan creates the dichotomy seen throughout his music of truths hard to acknowledge (i.e. being left alone and the ugliness of war) and the good silly things necessary to make life livable (i.e. human relationships).

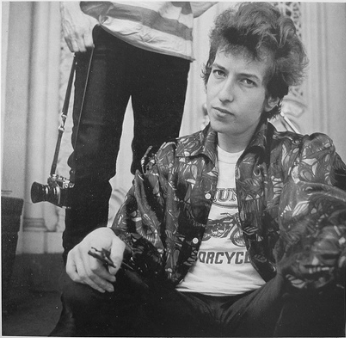

This past summer, my father took me to see the 1967 documentary Don’t Look Back shown at a theater in honor of Dylan’s 75th birthday. The film covers Dylan’s tour in England during 1965 and paints a picture of Dylan in his 20s: a bit conceited, captivating and unafraid to be opposing. He dresses in black and is perpetually smoking a cigarette, allergic to small talk and fluff. Watching the legend on screen was enthralling, and made me wish I lived in the 60s. The documentary is fantastic, deep and compelling. I recommend it almost as much as Dylan’s music itself. His lyrics are pure poetry and brilliance, and Dylan’s receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature proves his music will continue to challenge society’s notions of, well, everything. But for right now, just redefining what is considered literature will do.