By Katie Quinlisk

Follow columnist Katie Quinlisk as she sheds light on Fordham’s female history, one woman’s experience at a time.

On June 25th, 1924, Dean Wilkinson of Fordham Law received a letter from civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois. The letter was one of many in a series of correspondence between Fordham and Du Bois concerning twenty-three year old Fordham Law student, Ruth Whitehead Whaley.

Earlier that summer, Whaley received eight 100 percent marks on a series of papers. Grades like this were not unusual for Whaley, as she would graduate top of her class that same year. But, these papers were different because Fordham promised that the student who scored the highest average of marks would be awarded a prize: a set of law books donated by Corpus-Juris Publishing Company.

Whaley outscored her classmates by a large margin; however, when she visited the library to claim her prize, she was given what she described in a letter to Du Bois as “dampened enthusiasm,” “indirect and evasive answers” and an “averted gaze.”

The librarian told Whaley that “the fellows were kicking since some of them made 100 percent on the eighth set.” Whaley was told she would have to write another paper to compete with her male peers who had matched her mark on the eighth paper of the series.

Why did Fordham Law alter the rule last minute? Why was Whaley subject to another round of discernment? Perhaps Fordham had genuinely wanted to avoid student upset. Or perhaps Whaley’s 100 percent was suddenly not enough because she was a young, black woman studying in New York in the 1920s: a time and a place where discrimination looked more like withholding a well-deserved academic prize than the Jim Crow “separate but equal” segregation laws of the South.

Whaley decided to take action. She made charges against the University, and vocalized her grievances in a letter to W.E.B. Du Bois in hopes that Du Bois would publicize the injustice in The Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP.

The July 1924 issue of The Crisis reported the injustice. In a discussion of excluding black students from higher education, Du Bois wrote: “One of the best methods of getting rid of smart Negro competitors is to ‘forget.’ This is the brilliant invention of Dean Ignatius M. Wilkinson of Fordham University.”

Whaley was never awarded her set of law books. Alternately, as detailed in The Crisis, her name was left out of the winner lists of two other competitions and her diploma was withheld for her complaints. Whaley poignantly captured her situation as a young black woman in higher education in a letter to Du Bois that summer: “I am cognizant that even at Fordham University School of Law, winning is not always synonymous with receiving.”

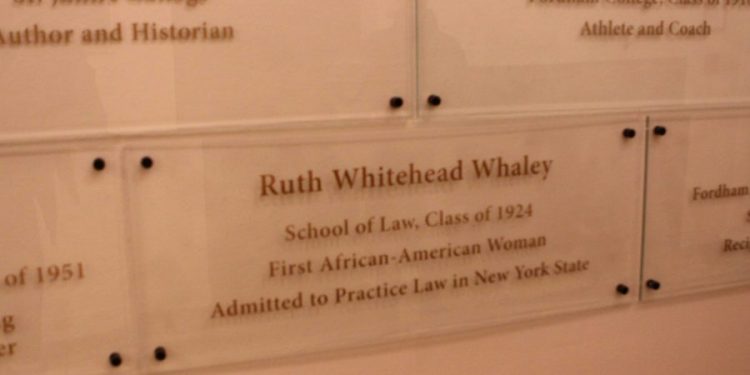

Though this injustice marred Whaley’s memories of Fordham, it hardly derailed her success. Whaley eventually received her degree, became the first black woman to graduate Fordham Law, and passed the Bar that year to become the first black woman to practice law in New York State.

Whaley was famous for her work in civil service law. She opened her private practice, served on the New York City Council throughout the 1940s and served as the secretary of the New York City Board of Estimate from 1951 to 1973.

Whaley served as the first president of the New York National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women and president of the National Council for Negro Women. She became involved in the Democratic Party post women’s suffrage throughout the 40s and 50s and returned to Fordham as a University Council member in the 1950s as an ambassador.

Whaley combated racial and gender discrimination in each professional role she undertook. Fordham finally honored Whaley in October of 2014 when she was inducted to the Alumni Hall of Honor. Today, Fordham’s Black Law Students Association bestows the annual Ruth Whitehead Whaley Trailblazing Alumnus Award to alumni who capture Whaley’s groundbreaking spirit—a spirit Fordham once tried to quell. Yale Law, the Association of Black Women Attorneys and Brooklyn Law School also offer awards in Whaley’s name.

Whaley would be 116 years old this February 2nd. We can’t sit down and speak with Whaley. We can’t ask her how she would proceed in today’s polarized America so wrought with racial injustice and gender inequality. We can’t ask Whaley how she would live and work beneath an executive branch that is so indifferent to the needs of its people and so blind to the promises of the Constitution that Whaley worked her whole life to defend.

We can’t ask her these questions, but Whaley’s answers can be found in the lines of her letters to Du Bois and her subsequent life work: “call out the injustice you see, and fight with all you have to end it.”

This is a beautiful written article on my Great Grandma. I can see my grandfather Herman Whaley smiling saying to me. Your grandma moved mountains.

I would like to say thank you to the person who wrote this article.

I am from Ruth Whitehead Whaley’s hometown of Goldsboro, North Carolina. I’m in the early states of writing a book about her life. Would you grant permission for me to use your wonderful write-up about her? This will not be my first published book under the author name Sherwood Owl Williford. I also wrote a column for the local Goldsboro News Argus for more than seven years. One of those columns was about Mrs. Whaley. I would be happy to share a copy with you should you be interested.

Thank you

Sherwood Williford

919 440-8811