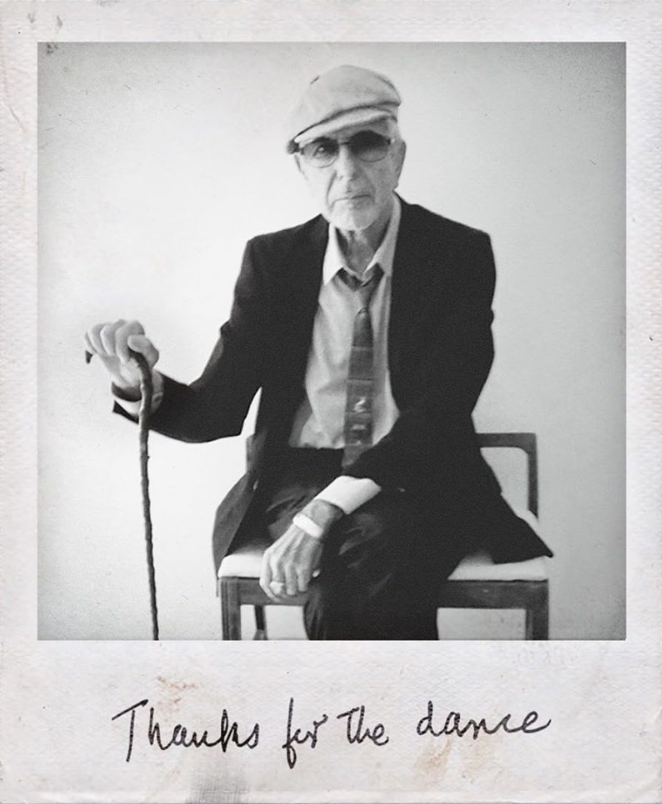

Leonard Cohen’s “Thanks for the Dance” Reopens Grief’s Wound

Leonard Cohen’s “Thanks for the Dance” Reopens Grief’s Wound

Courtesy of Leonard Cohen's official Instagram

Courtesy of Leonard Cohen's official Instagram

November 30, 2019

Hang on for a minute...we're trying to find some more stories you might like.

Email This Story

When a loved one exits the picture, a gash rips into ourselves. As the wound heals, a scar forms, and when a reminder of that loved one arises, the scar stings and may open back up.

Such is the case for Leonard Cohen’s “Thanks for the Dance,” posthumously released on Friday, Nov. 22. The new nine-song album completes Cohen’s vocal recordings from outtakes of 2016’s “You Want It Darker” and serves as its follow-up. Some of the tracks were originally included in Cohen’s final book of poetry, “The Flame,” released last year.

Despite leaving the work unfinished, “Thanks for the Dance” is undoubtedly Leonard Cohen. “Moving On,” one of the poems from “The Flame,” concludes his romance with Marianne Ilhen, his ’60s fling and inspiration for “So Long, Marianne.” Written after her death and only months before his own, Cohen wades in sentiment; “And now you’re gone, now you’re gone/ As if there ever was a you/ Who broke the heart and made it new/ Who’s moving on, who’s kidding who.” Yet, with the passage of time, he is able to take a step back and take an objective awareness of their situation: “Your beauty ruled me, though I knew/ ’Twas more hormonal than the view.”

An equally personal song, yet not as heart-wrenching for long time fans, is “The Night of Santiago,” a new kind of one-night-stand Cohen track. “Though I’ve forgotten half my life/ I still remember this,” he assures and whispers in a deep, aged, yet clear, croak of a voice. The original “soft boy,” exhibited in “Chelsea Hotel No. 2,” “Leaving Green Sleeves,” “Lady Midnight” and more, has returned and grown old here: “I gave her something pretty/ And I waited till she laughed/ I wasn’t born a gypsy/ To make a woman sad.”

Other new songs such as “Puppets” and “The Hills” touch on the reality Cohen saw toward the end of his life. Beginning with “German puppets” and “Jewish puppets,” “Puppets” connects the World War II era to the now; “Puppet presidents command/ Puppet troops to burn the land,” while puppet lovers turn away and puppet readers shake their heads and go to bed. On a personal level, “The Hills” explains Cohen’s current state — “I’m living on pills/ For which I thank God” — and, without dwelling on himself, discusses what may happen when Cohen passes: “But I’m not allowed/ A trace of regret/ For someone will use/ The thing I could not be.”

The line makes sense for the album’s final product — his words were used for a thing he could not finish. And that is the only place where the record falls short.

Most of these songs are just spoken poems with instrument tracks underneath them. While Cohen’s work leaned on that toward the end of his life and career, those songs were always intended to be released that way and that’s why it worked. Despite his son, Adam, and former co-writers such as Anjani Thomas adding compositions that they felt reflected Cohen, there is always the question of if the songs were ever meant to sound the way they do now. To sit and listen to “Thanks for the Dance” is to desire what Cohen might have done with these poems had he had the chance.

According to Adam Cohen to The New York Times, this was just the case — that despite Leonard Cohen’s best efforts, it was ultimately Adam’s job to finish the deed. Such is the unfortunate nature of posthumously released works. We get the taste of the artist’s life coming back to us, only for it to be cut short by the bitter reminder that there could have been more had they not been mortal. “Thanks for the Dance” is another example of how a musician’s work is tragically finite, as is life.

Copy Chief for Volume 101.

If you want a picture to show with your comment, go get a gravatar.