Sunday night’s episodes of “The Last Dance” are the most emotional of the series. The first 15 minutes of episode seven delve into the sudden passing of Jordan’s father — gunned down on the side of a highway in North Carolina while taking a nap in his car — during the summer of 1993. Several reporters, in a series of disgusting acts, tried to connect James Jordan’s death to his son’s issues with gambling and the NBA meting out a potentially-devastating punishment to the league’s best player. This theory is disproved multiple times in the documentary.

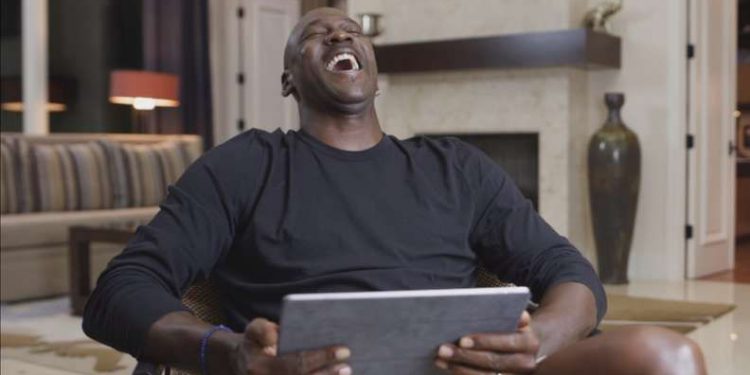

Michael Jordan, understandably, gets emotional talking about his father and their final conversations before his untimely death. The relationship between father and son leads the greatest basketball player on Earth to prematurely retire from the sport and take up a career with baseball’s Chicago White Sox, which would last only a year in the minor leagues before being cut short by that year’s players’ strike. However, the discussion of his father’s murder is not the most emotional we see Michael Jordan over the course of these two hours. No, the most emotional moment in Jordan’s interviews for “The Last Dance” — I’m excluding the shot of him crying after winning the 1996 Finals because that isn’t new footage — has to do with him talking about why he treated his teammates the way he did.

It’s hardly a secret that Jordan was a ruthless competitor. Former teammate Will Perdue put it more succinctly: “Let’s not get it wrong. He was an a–hole.” But, in being an a–hole, he got the most out of his teammates, even though it could be difficult to play with him. We saw traces of this in episode four, when Jordan teases teammate Scott Burrell and calls him an alcoholic to both his face and, 22 years later, millions of viewers. Burrell is one of Jordan’s main targets; by being tough on Burrell, he can unlock some of the potential he showed as a college player at UConn.

But Burrell, by Jordan’s admission, is a really nice guy. Burrell takes Jordan’s ribbings standing up, even tolerating Jordan calling him a “h–” in multiple practices. In 1995, with the Bulls building up to the greatest season in NBA history, Bulls coach Phil Jackson sensed Jordan’s angst in practice. Jordan had returned to the Bulls at the end of the prior season, but Chicago fell to the Finals-bound Magic in the second round of the playoffs. Jordan was mad, and Jackson knew it, so he put Steve Kerr, the shortest contributor on the team, on him in practice. On one play, Kerr fouled Jordan, so the game’s best player swung back around and hit him in the eye. Jackson, ever the master leader of the team, kicks Jordan out of practice and maintains his squad’s respect.

But there’s a method to Jordan’s jerkish madness. He needs to maximize the potential of his teammates because he needs them to win championships. In the same token, he also needs motivation, which is difficult when you’re the best player on the best team. Not to worry, though. Jordan had a plan for that.

Any insult, perceived or real, was potential fodder for Jordan’s memory bank. Call it an inferiority complex, a weird character trait, whatever you want. But it worked. We’ve seen him bristle at being compared to Clyde Drexler and object to being criticized for a late night trip to Atlantic City, both of which a lot of players wouldn’t think about. Jordan thrived off this motivation, and it didn’t particularly matter where it came from.

This hard-nosed competitor can be contrasted with the broken man found at the beginning of episode seven. After his father’s death, Jordan retires to play for the White Sox; he makes it to spring training and plays the 1994 season in AA. Jordan hits just .202, but he hadn’t played baseball for the past 14 years. That’s an objectively impressive feat, and his AA manager, Terry Francona, said that with 1,500 at-bats, Jordan could have made the big leagues.

However, with the 1994-95 MLB players’ strike, Jordan rightly refuses to cross the picket line and comes back to basketball. This underscores the theme we discussed last week: Jordan had a competition problem. He got burned out with basketball, so he seamlessly transitioned to baseball, with a work ethic one of his coaches said was unlike anything he had ever seen. His numbers weren’t impressive, but in context, the fact that he ever had any success was impressive.

But upon returning to the basketball court, he thrives off of insults and slights. He returns to the court wearing No. 45, his baseball number, and not his old No. 23. This was partially because he wanted to and partially because the Bulls had retired No. 23 when Jordan initially hung up his sneakers in 1993. After Game 1 of the second round of that year’s playoffs, Nick Anderson said that 45 didn’t explode the same way 23 did, and sure enough, Jordan was wearing 23 the next game.

Fast-forward to 1998, when Jordan’s Bulls are taking on the Charlotte Hornets, led by former Bull B.J. Armstrong, in the second round of the playoffs. In Game 2, Armstrong sinks a jumper over Jordan to sink the Bulls and tie the series at a game apiece. Three games later, the series was over, with Jordan averaging over 30 points per game over the Bulls’ next three wins. Jordan was triggered by Armstrong celebrating in his and Jackson’s face. Armstrong didn’t necessarily do anything wrong, but he woke up the sleeping giant. Against Michael Jordan, that’s something you never want to do.

But Sunday’s episodes weren’t just about Jordan’s pettiness, which is one of the main takeaways from “The Last Dance.” There are many subplots in these episodes, and many of them either could have been or already are their own documentaries. We have James Jordan’s death, his son’s retirement, Jordan’s competitiveness, his tenure in baseball and his bullying of Scott Burrell. There was also Scottie Pippen sitting out the final play of a playoff game because Jackson didn’t draw up a play for him.

But my main takeaway from Sunday night was Jordan’s competitiveness and his willingness to go to any lengths to win. He often thrived off of insults, and he always got the most out of them.

One story from “The Last Dance” illuminates this quite well. One night late in the ‘92-’93 season, the Bulls are taking on the then-unfortunately-named Washington Bullets in Chicago. The Bullets are bad, but second-year pro LaBradford Smith has a coming-out party, with 37 points in a game his team can’t quite win. Smith’s 37 points represent a bizarre one-off, he would never score more than 17 points in a game for the rest of his career. But on that night, he can’t miss, and Jordan struggles. However, the Bulls win. After the game, Smith approaches Jordan and says “Nice game, Mike.”

Jordan objects to the youngster’s eagerness to come up to him, and luckily for the Bulls, they get to play Washington the next night in the nation’s capital. Jordan is so offended by Smith’s “nice game” quip that he sets out to match his game total from the night before in the first half. Sure enough, he comes up just one point short, with 36 first-half points. Smith scored 15 points in vain and the Bulls won by 25.

Smith had committed the cardinal sin of playing against Michael Jordan, which was to insult him. There’s just one issue: Smith never did insult him. Jordan made the whole story up.

Other Things…

More on the final two episodes of “The Last Dance” next week. I hope you’re enjoying this show as much as I am. Come back next week, and keep in mind that Jordan punched Kerr in the face because I guarantee you it will come up again.