By Joseph Felix

I am pleased to announce that figure skating, as documented through the lens of Craig Gillespie, is not the glossy-coated, sparkly sport we know it as — it is completely badass. The gritty I, Tonya throws away the perfect protagonist in favor of a redneck underdog with a supporting cast that comes to compete.

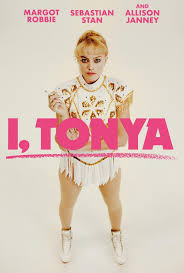

The Academy Award-nominated biopic follows Tonya Harding (Margot Robbie) and the subsequent trials she undergoes to become a world-class figure skater.

This includes enduring the verbal abuse of her mother LaVona Fay Golden (Allison Janney), the physical abuse of her ex-husband Jeff Gilooly (Sebastian Stan) and the “white trash” perception others have of her on and off the ice. With the 1992 Winter Olympics fast approaching, Harding hatches a plan to derail her opponent that goes hilariously and dangerously awry.

Harding is most associated with the infamous attack on figure skater Nancy Kerrigan at the 1994 U.S. Figure Skating Championships in Detroit. The attack, which Harding and her associates were accused of orchestrating, propelled Harding to international infamy and painted her as a violent, unhinged competitor who would do anything to win the gold.

She was, however, far from an untalented rookie looking to incapacitate a much stronger, well-heeled opponent. Harding received the silver medal for her performance at the 1991 World Figure Skating Championships in Munich, where she also became the first American woman to complete the triple axel at an international skating competition.

Further, she placed fourth at the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville, France. However, it was the Kerrigan attack which has continued to define and haunt Harding’s public image.

In I, Tonya, Margot Robbie refuses to shy away from completely inhabiting Harding, giving the most convincing performance of her career since playing Naomi Lapaglia, the Brooklyn bombshell in The Wolf of Wall Street.

Her smack-talking, messy haired persona can seem larger than life, a detriment when over-emphasized. But Janney, who masters the cold-hearted mother, reels her back in, justifying every misstep with a stony look of disapproval.

Stan shares an amusing on-screen chemistry with Paul Hauser, Stan’s idiot cohort who breaks the more serious scenes of the film and insists it should be considered a dark comedy.

I, Tonya is an underdog film that flips the script on its protagonist. You want to sympathize with the main character, who asks that her odds be evened, her childhood be corrected, her life be better, but all without reason.

Harding, similar to her philosophy about truth, knows there “is no reality but your own reality.” She smiles through the pain, skates to ZZ Top, takes whatever praise she can and carries on. Since the release of I, Tonya, Harding has not been afraid to address her past controversies.

In a January 2018 article by The New York Times entitled “Tonya Harding Would Like Her Apology Now,” writer Taffy Brodesser-Akner details that, in terms of Harding’s story, “[t]here are facts, and then there is the truth.” Throughout the interview, Harding recalls her version of her life’s events.

But despite Harding’s willingness, perhaps desire, to speak to the press, Brodesser-Akner asserts that much “of what [Harding] said wasn’t true.” Here lies the question at the heart of I, Tonya: what is the nature of truth? And if you happen to stumble across it, does it matter?