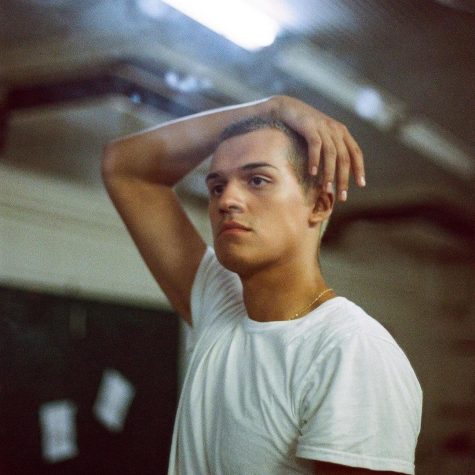

Fordham Junior Jacob Bartz Begins Research Venture

October 21, 2020

Junior year is a strenuous year for all collegiate students. As classes for a major tend to become more specific and likely more challenging, there is additional pressure to get internships and really think about life after graduation.

And for STEM students, there is also the huge undertaking of juggling scientific research.

Just ask Jacob Bartz, FCRH ’22, who has recently dedicated much of his time to the research of cardiomyopathy. This condition makes it harder for the heart to pump blood to the rest of the body.

It should be noted that, coincidentally, this article’s author happens to have a form of this heart condition, specifically hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Bartz and the graduate student he has been working with are taking a very interesting route to find more information about cardiomyopathy.

“I’m assisting grad student Kate Migunova with research studying cardiomyopathy in fruit flies in hopes of better understanding how it affects humans,” Bartz said, explaining the process by which he and Migunova are studying this human disease.

“We know that cardiomyopathy is caused by genetics in both humans and flies, so hopefully by studying the fly genes, we can learn more about how the disease affects humans,” said Bartz. “In my free time, I’m researching articles about cardiomyopathy in both people and flies so that I can better understand what I’m assisting with in the lab.”

That research in his spare time combines with hands-on research for what Bartz describes as a total of six to seven hours. That’s a lot of time to study a rather specific subject. Luckily, Bartz has had people to guide him along this intricate path of research.

“My academic advisor, Dr. [Edward] Dubrovsky, encouraged me to enroll in his genetics course last spring after we met several times in the fall semester and got along really well,” Bartz continued.

“I’ve always been interested in genetics, but taking his course and talking to him about the subject made me want to study it more in depth and work with Dr. Dubrovsky.”

Bartz’ enthusiastic entrance into a research project was, of course, like everything else that was supposed to commence earlier this year, halted by COVID-19. Bartz has seen the brunt of the virus’ inconveniences to people, having spent five weeks of this year in quarantine between returning home to Dallas, Texas, studying over the summer at the University of Hawaii and coming back to the Bronx to be on campus at Fordham this fall.

But these setbacks did not stop Bartz’ relentless drive to do some kind of research.

“Over the summer, I reached out to [Dr. Dubrovsky], and we had a Zoom meeting to catch up and discuss research opportunities this fall.”

It was through this relationship with Dr. Dubrovsky that Bartz was able to get on board with Migunova’s research. Bartz said that Migunova has been “very kind to [him]” in the process of allowing him to be a part of the project. “It’s a joy to work with her,” he said.

Such a complicated premise for research requires an equally complicated process for examining cardiomyopathy in fruit flies, Bartz explained.

“In the lab, I get to operate the campus’ confocal microscope, which is located in a dark room in Larkin,” he said, divulging the incredible amount of meticulous precision it takes to understand such a machine. “I’m currently learning how to operate the incredibly complicated software that goes along with it.”

The microscope as a machine is no small undertaking, and neither are the study’s subjects.

“The microscope uses a series of lasers to assist in identifying the dissected hearts of fruit flies that we’ve prepared and stored,” he said. “After configuring the lasers to appropriately display the hearts, I have to use the microscope to construct a map of the slide that I can navigate around, which requires me to identify and scan every other heart on the slide.”

“Wild type fruit flies have a predictable amount of cells in each section of the heart,” Bartz said. “By counting the abnormalities in mutant cardiomyopathic flies, we can learn more about the different ways in which the phenotype can present itself.”

Such precise work can often make a person lose sight of the importance of what they’re actually doing and feel like they are simply completing a task. But for Bartz, a rather optimistic person, that sense of the bigger picture doesn’t seem to be too far away.

“By using the fruit flies as a model organism to study genetic abnormalities, we can shed a lot of light on how the genetics of cardiomyopathy in humans works,” Bartz said, himself shedding light on the importance of the work he’s doing with Migunova. “Research on Drosophila could assist with understanding how cardiomyopathy is caused, the different ways that it can affect a person, and potentially how to treat it.”

The research done at universities, for graduates and undergraduates alike, can truly bring positive change to the world, and for Bartz, it’s all about the work.

If you want a picture to show with your comment, go get a gravatar.