Overly-Familiar Profundity and Poetics: “Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass” by Lana Del Rey

In her debut poetry collection, Fordham alumni Lana Del Rey (FCRH ’08) presents a faltered look into the life of an American superstar. (Courtesy of Facebook)

October 28, 2020

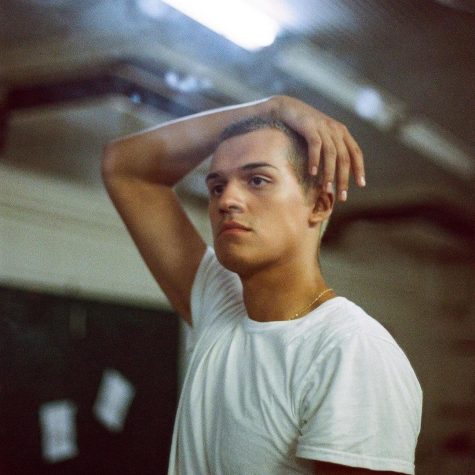

Named by Bruce Springsteen as “simply one of the best songwriters” in Rolling Stone Magazine, Lana Del Rey, also known as Elizabeth Grant, FCRH ’08, is an original songwriter whose work examines everything from American nostalgia to heartbreak. In her newest project, “Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass,” a collection of poetry written by the singer, Del Rey uses flowery imagery and nostalgia to create a collection that does justice to the profundity present in her music.

During Del Rey’s time at Fordham University, she recorded songs like “Fordham Road,” a melancholy anthem to her college experience recorded during her sophomore year. Since then, Del Rey has released five studio albums and has been nominated for five Grammy awards. This melancholy demeanour characterizes much of Del Rey’s newest works as well. Her album “Norman F—— Rockwell” was a critic’s favorite in 2019 and continues to be one of the singer’s most profound looks into her life of tumultuous relationships with love and fame.

After stunning critics with “Norman F—— Rockwell,” Del Rey published “Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass,” a collection of poetry, photographs and paintings published in July 2020 by Simon & Schuster. While met with widespread love from fans, Del Rey’s collection fails to show more of the singer’s nuanced perspective, opting instead for flowery poetics that overcomplicate beautiful stories.

The collection’s opening poem, also titled “Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass,” depicts a young girl named Violet playing in the grass. As Violet descends into a backbend, Del Rey describes her as “grinning wildly like a madman / with the exuberance that only doing nothing can bring / waiting for fireworks to begin.” Here, readers understand what this collection is about: falls from youth, the complacency of American minds and the anticipation of entertainment on our media-addicted persons. This image is beautiful, and begins the collection beautifully. However, as the collection progresses, Del Rey begins to lose these themes and complicate these simple, profound images.

An example of such overindulgent word choice is in “The Land of 1000 Fires,” which becomes an amalgamation of space-age imagery with love story tropes. While beautiful in stanza, Del Rey’s combination of images fails to produce a larger narrative about her desired point. We understand from her calculated, imagery-rich songs that love is complex for Del Rey — she is strong-willed, determined and complicated, making love an experience more than a destination. In “Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass,” Del Rey brings her experiences in the same framework as her songs, failing to explore something beyond.

Nevertheless, Del Rey’s typewriter and polaroid aesthetic is interestingly complimented by the presence of in-book notes on pages, illustrating the singer’s writing process and growth. While a glimpse into the career of the superstar, it shows more about her growth as a technical poet than as a person. And as a poet, Del Rey does not surprise her fans with anything new by sticking to her traditional lyrical style.

While beautifully complimented by art and pictures, “Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass” proves Del Rey has discovered her sound as an artist. Her sense of American complexities and heartbreaking love is what makes the singer “simply one of the best songwriters” but fails to bring anything new to the world of poetry. Although a fan favorite, the collection feels like an extension of “Norman F—— Rockwell,” refusing to indulge readers with a new dimension of Del Rey’s voice.

If you want a picture to show with your comment, go get a gravatar.